Stefano W. Pasquini

Some artists cross currents and decades with lightness, without getting fixated with a style, without closing their options within a set code. Stefano W. Pasquini is one of such artists. For over fifteen years he’s been challenging the international scene without constraint, showing off works that would shake the most fearless hacker. With years spent in London, “grown up” in New York, and back in Bologna (where he succeeded his father – thus the middle W., typical of someone destined to success), Pasquini knows that art is a constant challenge with oneself, that victory will only be met when, calmly but surely, he would have obtained a true result, not the usual consent of relatives and friends, as it often happens.

So Pasquini doesn’t worry about changing styles and contents: he goes from interactive performances – like when, for example, he dressed like Spider-man, sitting on the floor of the streets of London – to the hard rock videos – like the one he’s in the woods stuck with his hands and feet onto the ground, shouting like a maniac. He’s also not afraid to return to paintings, portraying, with a fast and synthetic stroke, himself or people from the mass media zoo. Or eschews the indifference in order to approach politics, making works that range from portraying the statesman Aldo Moro in sculpture, as he was found (dead) in the trunk of a Renault in via Caetani, to a performance where a series of people raise on pedestals and wave their hands in the fascist salute. And then drawings, writings, collages, photographs: diverse forms of transient, spontaneous, creativity . Once upon a time this would have been described as lack of coherence. Nowadays it seems to be the instinctive and immediate reaction to the incoherency we witness daily on the news. Or in reality, which is almost the same thing now. Therefore, while the fascist performance youngsters climb the pedestal, art jumps off it to find itself in the midst of home things.

If one were to find a constant thread in all this, it would have to be, beyond the quality, in its quantity. This since 2004, when Stefano W. Pasquini decided to realize one artwork a day, be it a finished work or just a simple gesture, a remain of a little story in the path of life. He then took all this further and made it into a TV auction, one in which artworks are supermarket goods and words count more than images, and the vendor is an art critic turned into a natural born salesperson.

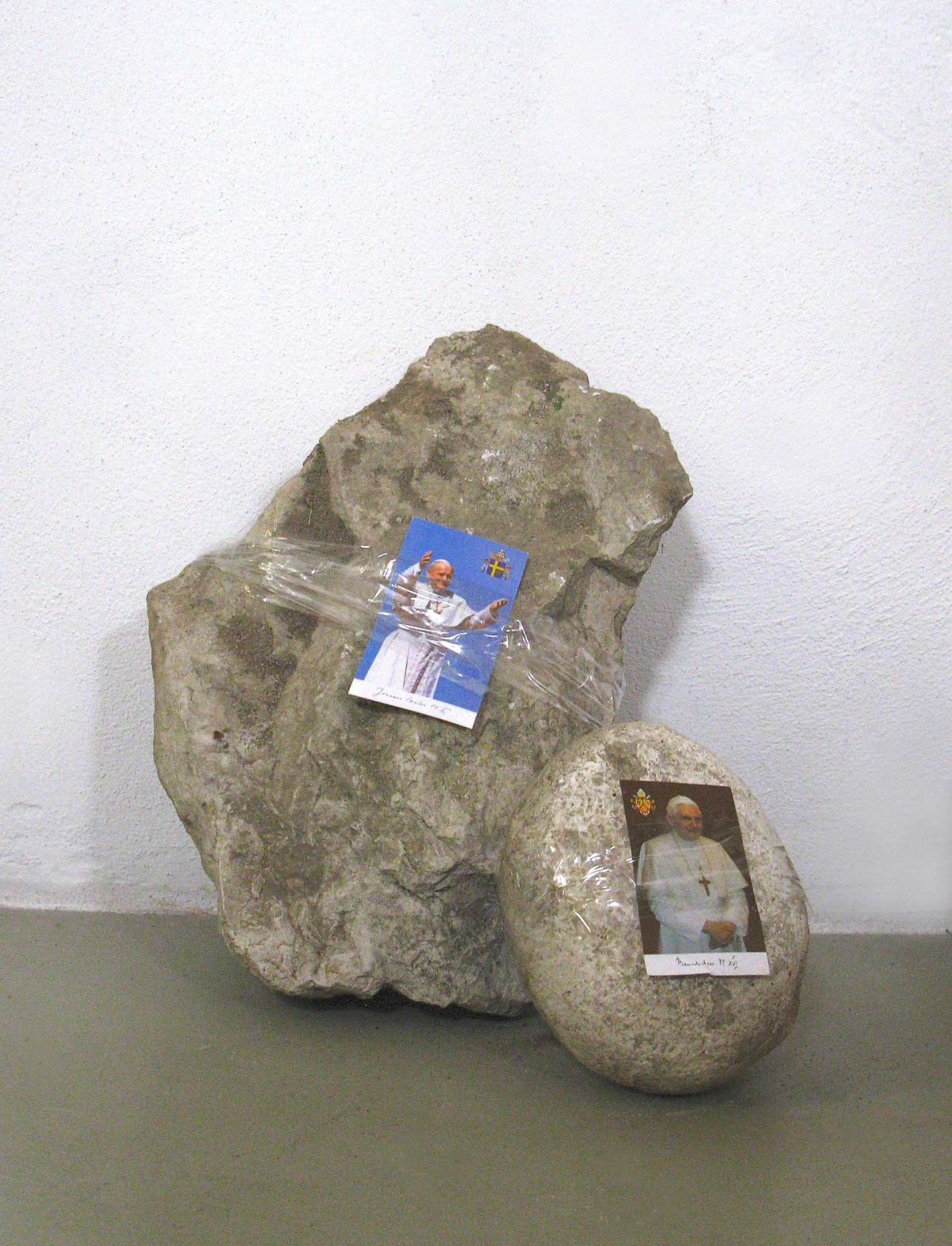

Art slides into playfulness and irony, even against itself.. Within the unsubstantial projects of Stefano W. Pasquini there is room also for a Facebook Biennale, a biennial where everyone can participate. Where by, after the initial launch. the problem is understanding how it will work, only to recognize that the exhibition is the Facebook group page, and the invited artists are whoever joined in, without any sort of selection. From this and other projects one can perceive how the artist is in debt with new technologies, their expansion and viral power, almost to the point of disappearing as author in order to leave the work with its own life, with an independent capability of expansion and definition. But then you have the twitches, the personal wriggles. These are where we recognise the artist. For example, the casual sloppiness with which Pasquini uses scotch tape to stick a holy effigy or an image of the Pope on a rock. A simple act, subtly brutal, that shows a precarious stability, as if the art work was just a passage, a temporary sign waiting for a bigger support, like a small monument by the side of the road to remember an accident that will soon be replaced with something in solid concrete. So there are works deliberately resembling the spontaneous creativity of an adolescent in his room: drawings, collages, jokes. A temporary wit that halts a moment in the evolution of life. In short, art for Stefano W. Pasquini is like a blog, a place to find and compare the incomprehensible sides of one self. So, if you were trying to find a constant path, or a typical feature, you could probably look in its temporarity, in the precariousness of his inventions. Take one of latest works, born first of all as an image, a sign that reminds of fear and risk, Frightening Figure, built as an unsafe little bridge made out of found wood boards. Or take a look at the many assemblages with which he realizes little monuments, lopsided structures where the naturalness of a piece of wood meets the artificiality of a lighter, or shreds of a medicine box. These are slender manifestations of instability, time breaks in the transiency of existence. There is also a melancholy streak in the vision of Stefano W. Pasquini. An intrinsic, dry melancholy, that does not lead to discouragement, but reveals the past as a place of unfulfilled hopes.

Are the Nineties really over? Those years full of concrete utopias, artistically and politically, from the No Global movement to the Young British Artists? Have we passed those years pregnant with ideas of infinite expansion, of the possibility of a democracy from below, of a real sort of communism thanks to the information freedom of the network? Nowadays we find out that Internet is not that open, that in many places censorship is king and the right of reproduction hinders research, that our society seems to be going towards a gelatinous totalitarianism rather than towards individual freedom, then yes, the Nineties are definitely over. And art has to emphasize this change. So if a few years ago a small drawing by Pasquini read Damien, let me be your Giacomo Grosso, today the closure has a different text: Once I was a YBA. Bitter redraft for someone who in 1992 had already the intuition of interviewing Jay Jopling.

Fabio Cavallucci , 2010

P.S. What about the Impressionists of the title? I forgot, what about them? Well, they are there to attract the public. Art, almost a business in the 21st century, needs refined marketing strategies… and Impressionism always works.

P.P.S. Don’t you think much of this vision of art and life? Well, I think it’s the most right and coherent with the times.